The Japanese invasion of Malaya during World War 2 took place on December 8th 1941, a day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Coming through the border of Thailand and Kedah at the northern point of Malaya, the Japanese army marched through Malaya within 54 days. The British army made their last stand on the island of Singapore, surrendering to the Japanese army on January 31st 1942.

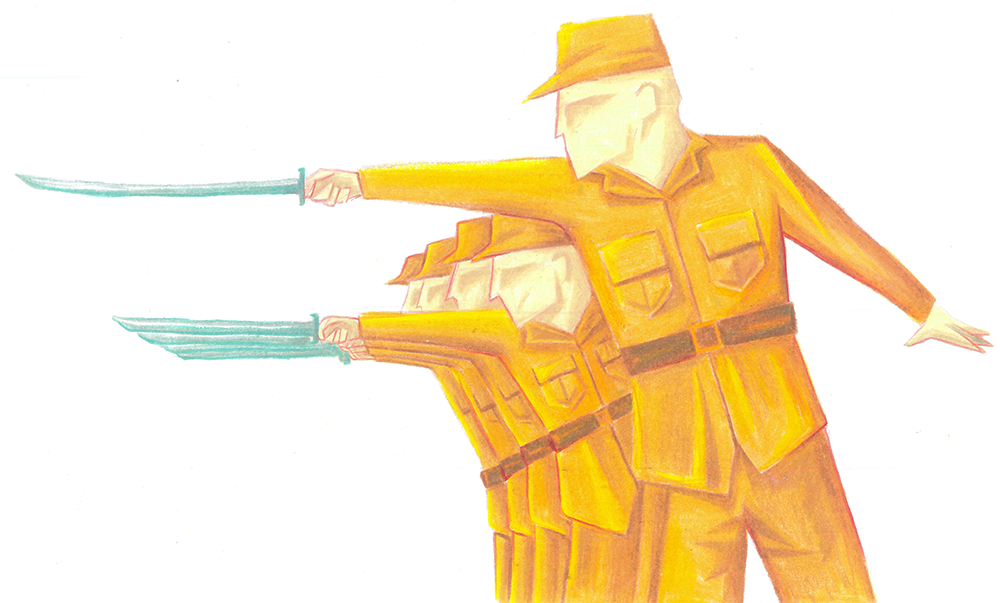

Upon their arrival to the Malayan continent, the Japanese targeted the Chinese population, ransacking and burning many Chinese establishments, torturing and killing Chinese men and women.

The Japanese army also banned Chinese schools and Chinese education during their occupation of Malaya. They executed any teachers and students who attempted to continue pursuing Chinese education. Such was the case at Chung Ling High School in Penang, where the school was turned into a interegotion, torture and execution camp, claiming the lives of countless teachers and students.

In retaliation to the Japanese occupancy, political parties such as Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) and Malayan Communist Party (MCP) were formed with a Chinese majority, participating in guerrilla warfare to resist the Japanese occupation of Malaya.

The most notable Chinese figure during this period was arguably Chin Peng, the leader of the MCP. Initially leading the party to resist the Japanese invasion, he then adopted an anti-British stance which led to the 1948 Malayan Emergency. The Malayan Emergency was a guerilla war between the Commonwealth forces and the Malayan Communist Party that went for 41 years.

During that period, Chin Peng attempted insurgency twice, yet ultimately failing both times. The party eventually laid down arms in 1989 and Chin Peng was exiled to Thailand, unable to return to Malaysia even after his death in 2013.

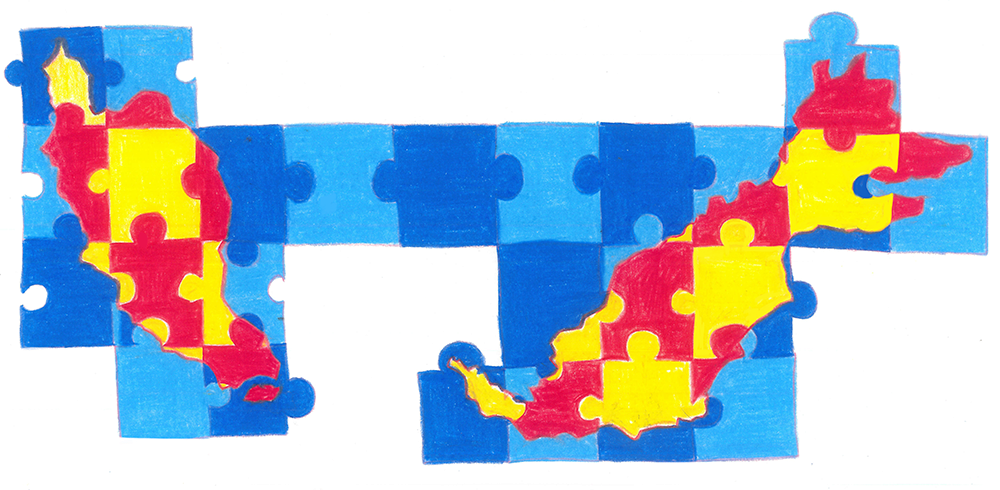

On August 31 1957, the Federation of Malaya achieved independance from the British Empire, with Tunku Abdul Rahman acting as the first prime minister. The Federation became a member of the Commenwealth of Nations, officialy marking the end of British rulership.

Just seven years later, on September 16 1963, the formation of Malaysia was put in place by combining Malayan Federation with Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore.

Singapore would later be expelled from the Federation in 1965 as racial tensions began to rise.

On May 13 1969, conflicts between Chinese and Malays occurred, leading to one of the blackest and most tragic days in Malaysian history. The events, now known as the 513 Incident, broke out during the aftermath of the 1969 general election, when Chinese opposition parties gained traction at the expense of the ruling coalition. Tensions had been rising between the 2 races, with the issue of economic disparity between Chinese and Malay, as well as Malay privilege, which added fuel to the fire.

On May 13, fist fights occurred between a travelling group of Malay and Chinese bystanders, escalating to bottle and stone-throwing. As the news spread, Malays taking part in a victory paraded broke off and headed to Chinese sections of the city armed with knives. 8 Chinese were killed in that initial attack, and the conflicts spread like wildfire throughout the region. While the Chinese were unprepared, they quickly formed groups and retaliated, attacking any Malays in sight. The burning and looting of Chinese shophouses continued for the next few days, with thousands of Chinese displaced from their homes.

By the time the riots had ended, 143 Chinese-Malaysians had been killed.

Today, Chinese immigration to Malaysia has stagnated, with people of Chinese descent being locally born. However, that number of Chinese-Malaysians have been decreasing over the years, due to lower birth rates and emigration. Many young Chinese-Malaysians are now leaving Malaysia for other countries, drawn towards the better economic and career prospects that exists overseas. Regardless, the Chinese population has left their mark in Malaysia’s history, shaping the country’s history and creating much of its rich vibrant culture.